Two weeks ago I wrote about the hypothesis of Harold Katcher (and others) that aging may be mediated by signaling molecules that circulate in the blood – hormones among them. Katcher’s idea for rejuvenation is to give older folks transfusions of blood plasma (with the white and red blood cells filtered out) from younger folks. This could require a large number of young volunteers, I said, so maybe we could make a start by identifying some of the differences between hormones in blood from older and younger humans. There are some hormones we have too much of, and others we have too little of as we age.

A timely news item: Steve Horvath, a biostatistician from UCLA, published an article last week in which he analyzed the way gene expression changes with age. A semi-permanent factor in gene expression is methylation of the DNA, and Horvath showed that you can pretty much tell how old a person is by using a statistical template he developed to analyze which genes are methylated.

This week, I explore a few hormones that decline with age. (Next week, I’ll cover those that increase with age.) Of those I’ve investigated, melatonin offers the best prospect for life extension benefits.

– – – – – – – – – – – – – – –

I take the position that aging is not a passive process of accumulated damage, but a genetic program, centrally orchestrated through the body on a schedule. It follows that signaling molecules that broadcast instructions through the bloodstream are likely to be messengers of death as we get older. There are too many signals to catalog, and biochemists are just beginning to unravel the web of their interactions. Some may be small RNAs and micro-proteins, in addition to the better-known hormones. Nevertheless, it’s worthwhile looking at those we know about.

Melatonin:

Melatonin is just the kind of circulating factor we’d like to evaluate. It is produced in the brain (specifically the pineal gland), and it is a high-level signaling hormone that affects gene transcription, with a cascade of lower-level effects.

This was the first hormone to be studied for anti-aging potential, and there is good evidence that supplementing with melatonin works to modestly extend rodents’ life span. Melatonin is an anti-oxidant, but in the tiny quantities that the deploys it, this is probably not significant. It is best known as a regulator of our diurnal sleep cycle. Young people generate melatonin in their bloodstream around the same time each evening, signaling the body to prepare for sleep; and melatonin levels stay high through the night, dropping off before it’s time to wake up. Older people have less melatonin at night. More older people than younger people suffer from sleep disorders. And some people who travel between time zones find that taking melatonin at the (new) bedtime helps their bodies to reset their clocks.

(In my personal experience, I find that 1 mg of melatonin helps me fall asleep at night. Side effects include morning “sand” in my eyes, exacerbation of apnea, and possibly an effect on dreaming – it’s hard to tell.)

“It may be that melatonin, when taken as a supplement, can stop or slow the spread of cancer, make the immune system stronger, or slow down the aging process. But these areas need more research,” says WebMD – a properly conservative assessment.

I’ve mentioned Vladimir Anisimov in the past – a Russian biochemist who has studied a large number of anti-aging interventions in his lab, and reports optimistic results, only some of which have been replicated outside his St Petersburg lab. He may be the world’s authority on the association between melatonin and slower aging. Here is his 2006 review of studies up to that time.

Melatonin is a potent neuroprotective agent, demonstrated in tests where animals brains are subjected to ischemia (oxygen deprivation). It has been proposed as a no-brainer for Alzheimer’s treatment [Ref1, Ref2, Ref3], and for Parkinson’s there is preliminary data [Ref1, Ref2, Ref3], though clinical evidence remains shaky.

Taken orally, it is easily absorbed and quickly boosts blood levels. Melatonin is cheap and convenient. In the mid 1990s, several books were published promoting broad benefits. Walter Pierpaoli led the charge. There followed the inevitable backlash, but when I review the warnings in these papers now, I find they have little substance. The worst they had to say was that melatonin needs more study. This remains true today, and melatonin’s chief drawback in this area is that it is unpatentable and too cheap to motivate any capitalist entity to invest in research.

Thyroxine and thyrotropin

Thyroxin is a hormone generated by the thyroid. Bet you knew that. Like melatonin, it is a high-level signal with lots of downstream effects. And as with melatonin, levels of thyroxine decline with age. A few studies have found association between low thyroxine levels and mortality, and with risk of brain aging diseases (PD and AD); but others find the opposite.

Thyrotropin is a related hormone, which stimulates the thyroid to produce thyroxine. There is better data associating low thyrotropin levels with disease in the elderly than there is for thyroxine. The Leiden 85+ study of mortality in the elderly found that mortality rates were higher in people who had high thyroxine, low thyrotropin. (Yes, that’s not a misprint: high thyroxine levels in older people might be a liability.)

There is no question there is such a thing as too much thyroxine as well as too little, and it is regulated in the body from moment to moment. Symptoms of too much thyroxine include anxiety, tremors and heart irregularity. So thyroxine is tricky, and it is wisely classed as a prescription drug, though it is a natural hormone. But there are thyroxine pills, available by prescription, prescribed for hypothyroid conditions; some people also use them for weight loss. Daily dosages in tens of micrograms. We rarely stop to think how exquisitely sensitive is our bodies’ homeostasis, that a signal far smaller than a pinhead can have major effects.

Carnitine and carnosine are two popular supplements taken for potential life extension benefits that can interfere with thyroxine uptake. A number of other supplements stimulate and support the thyroid. Without clinical symptoms, these may be more practical alternatives to thyroxine for now, but maybe someday we will know better how to optimize thyroxine levels in the body.

DHEA (dehydroepiandrosterone)

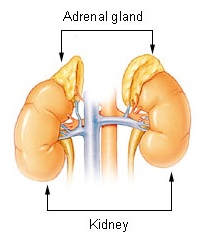

The most abundant hormone in the body when we are in our 20’s declines to a small fraction of its prevalence when we are old. At any age, males have more than females. Manuractured in the adrenals, DHEA is chemically related to sex hormones and steroids, and there is evidence that they are transformed into these forms in our bodies.

There are some studies showing cancer suppression in mice from DHEA. But DHEA is peculiar to human biochemistry, and it is scarce in mice and rats. This is a reason to question whether there is a basic relationship to aging, and also whether we can extrapolate from studies of DHEA in rodents.

Some human studies show lower rates of heart disease and cancer when DHEA levels are higher; others find no effect. If there is a benefit, it may be small enough or contingent enough that it is difficult to disentangle from secondary associations. Smokers tend to have higher DHEA levels.

“An early human study that pointed to possible benefits for DHEA came from Dr. Barrett-Connor’s group. They measured DHEA levels in blood samples taken from almost 2,000 men and women between 1972 and 1974 and looked at how many died from heart disease. In 1986, they reported that men with high DHEA levels were far less likely to have died of heart disease, while women with high DHEA levels were at greater risk. A more detailed analysis published late last year, however, showed that men with above-average DHEA levels back in the early 1970s were only 15% less likely to have died of heart disease, while there was no association between DHEA levels and heart disease in women.” (Ray Sahelian, 1996)

There is better evicence that DHEA has, for some people, a positive effect on mood and energy and possibly favorable body composition (more muscle, less fat). Life Extension Foundation emphasizes that dosing should be done in conjunction with blood tests, because of individual differences in absorption and in natural DHEA levels.

Mayo clinic says: “No studies on the long-term effects of DHEA have been conducted. DHEA can cause higher than normal levels of androgens and estrogens in the body, and theoretically may increase the risk of prostate, breast, ovarian, and other hormone-sensitive cancers. Therefore, it is not recommended for regular use without supervision by a licensed health professional.” Nevertheless, it’s sold over-the-counter.

Men and women respond differently to DHEA because it has a greater propensity to be turned into male hormones. In a UCSD clinical study, hormone levels were monitored in men and women during a six-month course of DHEA. Male hormones in the women but not the men rose to unnaturally high levels,

Others:

I’m not going to talk about growth hormone. HGH can make you feel good in the short run, but it is a life-shortener in the end. “Despite more than a decade of finding numerous ways to slow aging in mice, the longest-lived genetically altered mice are still those that lack the genes for growth hormone receptor (GHR),” [Source]

Sex hormones decrease with age, but from a theoretical perspective the evolutionary function is to cut off fertility, not to raise mortality. A lot of study has been done of post-menopausal hormone replacement therapy and mortality from cancer and heart disease, and the story has no simple message. The same is true for (male and female) sex hormone levels in males.

Some of the biochemical changes with age take place within the cell, unrelated to whole-body signaling. For example, CoQ10 (ubiquinone) is manufactured and consumed in each cell. It does not qualify as a hormone or signaling chemical because it is not circulated. As for CoQ10, there is less of it as we age, and probably the body suffers for that. Certainly the capacity of mitochondra to generate energy for us diminishes with age, and a shortage of CoQ10 is a logical candidate. Oral administration of CoQ10 has not produced life extension in animal experiments. Vladimir Skulachev (University of Moscow) has an ingenious way to target CoQ10 to the mitochondria, and he has succeeded in increasing life span in lab rodents using what he calls SkQ, which is a CoQ10 molecule modified with a mitochondrion-seeking tugboat on the front.

Respecting the wisdom of the body – not!

Editorial comment: There’s a habit of conservatism in medical thinking that has imposed too high a burden of proof for DHEA and melatonin and thyroxine, based on a vague notion that the body knows what it is doing, so if we have less of it as we age, then probably less of it is good for us. This is the way people think before they realize that the body’s purpose is to kill itself, slowly but surely as we get older. If we want to live longer, we are going to have to oppose programmed biochemical changes that come with age.

Today and tomorrow

I can recommend melatonin for now, and hope that study in coming years focuses on other promising targets for intervention, especially Anisimov’s small peptides. There is no barrier to studying difference between blood factors in young and old people. It could be done now at modest cost. For example, small peptides could be catalogued in blood samples from 100 young people and 100 old people, and consistent differences would be easy to spot. The same could be done with short RNAs. What else to look for? I’m sure the biochemists have better ideas than I have.

Discover more from Josh Mitteldorf

Subscribe to get the latest posts sent to your email.

You know of the old and young mice with joined blood systems? The old mouse healed like a young one? Looks like there is a blood borne factor for some parts of youngness. I think a few years of looking for it will discover that factor and then I have no doubt we can find a way to make enough of it not to need young blood transfusions.

Oh, wait, that was YOU who told about the young and old mice with a joined blood system. I bet you still remember from two weeks ago.

Thanks for the excellent thought provoking articles.They continue to help me as a student of Anti-Aging and Interventional Cardiology.I wonder with all this 100mg of oligomeric Proanthocynadins could help in a good active life.

Regards

Dr.Muhammad Asif

changes in levels of cytokines with aging here: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/26080062