I am a passionate life extensionist. I am a passionate conservationist. I have been living with a contradiction, increasingly stark as my understanding of both these causes, and my commitment to them deepens.

Nearly 20 years ago, I first became convinced by a variety of experimental evidence that aging is programmed into our genes by evolution. It was five years after that that I had my first inkling how this could be. This led to a study of evolved population regulation, and I became exquisitely aware of the entanglement of evolution and ecology.

Why would evolution create something as antithetical to the interests of her children (individually) as aging unto death? A gene for aging is the opposite of a selfish gene. And yet it is abundantly clear that we have genes* with no other purpose than to kill us. Suicide genes.

My principal contribution to the field of aging research is the Demographic Theory of Aging, which says that aging evolved for the purpose of population stabilization. There have been other theories of programmed aging in the past, usually based on the need for population turnover to assure adaptability, ongoing evolution and the ability of a population to change as conditions change. What I demonstrated (first in a 2006 paper ) is that population dynamics provides a far more potent selective force than this. Yes, the need to maintain population diversity and to change over time is certainly real . But (for animals) the need to avoid population overshoot and subsequent crashes to extinction is far more urgent (not so for plants). All animals depend on an ecosystem, and if they grow faster than their ecosystem, they are doomed. Not doomed “eventually” in some abstract, far-off morality tale. They are doomed within a generation or two.

Every animal population must have the latent capacity to grow quite rapidly in a pinch. You can translate this to mean, roughly, that a population must be able to double in each generation when it is threatened or expanding freely into a new and fertile environment. Human families in indigenous cultures can produce 6 or 7 babies, 4 of which survive to breed. Roundworms can lay 300 eggs, 2 of which survive to breed**. And, of course, microbes reproduce by cloning and double exactly with each generation.

art by Maddy Ballard

But the doubling of a population that is already at carrying capacity can spell disaster. Every blade of grass is eaten, or every rabbit is hunted, or every tree is denuded, and the ecosystem crumbles from the bottom up.

An ecosystem is a food web–predator and prey, the predator’s predator and the prey’s prey, multiply, connected and entangled, in an intricate network of interdependencies. Stability of the network does not come for free. There is no “invisible hand” that produces a grand harmony from a thousand selfish actors. Rather, there is deep and ongoing coevolution. Natural selection has taught each species cooperation and restraint via a billion years of tough love. Those species that overreached to trash their own ecosystems brought their ecosystems crashing down, and their rapacious behaviors died with them.

(To this thesis, scientists in diverse fields say, “of course–that’s the essence of natural selection”. But professional evolutionists have been trained to deny that such processes as this can occur. Many still insist that evolution can only work to promote selfishness, never cooperation.)

Ecosystems are resilient. There is an ability to bounce back after disturbance, from a natural disaster or the loss of a keystone predator. This, too, is a property honed by natural selection, a strength of the community that has evolved gene-by-gene in its component species. The unexpected happens, and the ecosystem has to deal with it. Those ecosystems that can’t recover from an invasion or a decade of bad weather have long ago disappeared from the biosphere.

But recovery of an ecosystem requires time. Bouncing back after a small disruption may require a dozen years or a dozen dozen. Bouncing back from a major geologic or climate event requires thousands of years. And in the history of multicellular life there have been five major extinctions. Each time, the biosphere required tens of millions of years to recover.

We are now in the midst of the sixth global extinction , and as far as archaeology can tell, the anthropocene extinction is as deep and as rapid as any the earth has seen.

And how did we get here? I believe the road to the Sixth Extinction was paved with ideology. I speak not just of the Biblical ideology that says it is our place to “be fruitful and multiply, and fill the earth and subdue it; and have dominion over the fish of the sea and over the birds of the air and over every living thing that moves upon the earth.” [Genesis 1:28] There is also the dominant version of Darwinian ideology that admits no explicit need for cooperation, but celebrates the creative power of selfishness. Worst, perhaps, is the capitalist ideology that assigns no value to anything that cannot be translated into dollars , and that demands perpetual growth in order to support a return on investments.

Does Life Extension Contribute to Overpopulation?

Well yes, of course it does. Human history since the advent of agriculture has been a quest to tame the environment, to substitute predictable domestication for nature’s wild ride. We have done this to avoid death and the risk of death.

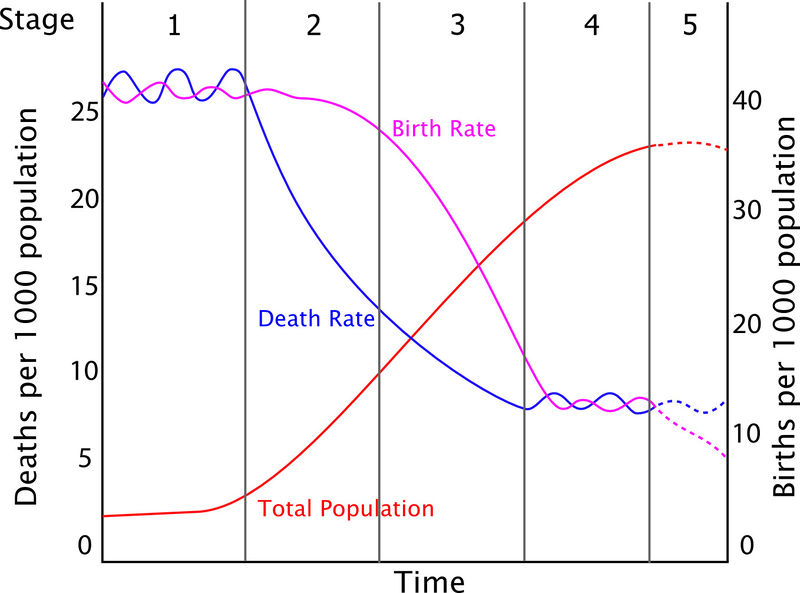

But only since 1840 has there been any significant advance in human life expectancy . Our animal nature has responded reliably, compensating with a lower birth rate that not even fundamentalist religious ideologies have been able to hold back. But between lowered death rates and lowered birth rates there has been a gap of 30-40 years, leading to a dramatic growth in the human population. Aldous Huxley recognized this pattern as early as 1956. “What we’ve done is ‘death control’ without balancing this with birth control at the other end….”

Currently, Africa is the last continent where technology is finally moving in to increase life expectancy, and the African birth rate is coming down, but not fast enough to avoid devastating population increases. Over the next 30 years, the population of Africa is expected to double from 1.1 billion to 2.4 billion, a larger absolute increase than the rest of the world put together.

Life span in 1840 was about 40 years in the world-leading European countries. In 2015 it was 83 in Japan and Scandinavia, the present world leaders. And indeed, the increase has been quite steady and gradual, so that “one year for every four” is an accurate characterization. For the first 120 years, increased life span was a story of early deaths prevented. Before about 1970, all this progress in life expectancy was achieved by preventing people from dying young, benefits reaped from antibiotics, hygiene, and workplace safety. But since then, a remarkable thing has happened: the maximum human life span has risen, and continues to rise at an accelerating pace (as recounted by Oeppen and Vaupel). What is more, people in their seventies and eighties are healthier today than ever before. Although there are dramatically more seniors in the population, the proportion of the population in assisted living and other dependent care situations is not rising. This is just what we wanted–we are staying active and healthy longer, retiring later, delaying the ravages of old age and “compressing morbidity” of late life into a shorter endgame.

Gratifying for the individual–treacherous for the collective

World population at 7.3 billion is about ten times what it was in 1800. A tenfold increase over 200 years is a good run, but it’s not unusual in the context of the biosphere’s history. Far from it. Bacterial populations routinely expand by a factor of a million. Insect populations can boom and crash. There are many examples even of large animal populations that have grown far faster than Man.

But other population increases have been local, while the rise of mankind has been all over the planet. We are now a global population, adapted to living in deserts and jungles, snow-capped mountains and forests and fields. We mow them all down, or burn them, or pave them over. Man has put many other predators out of business, from mastodons and sabre-tooth tigers to moas to a slew of toads and salamanders in the present age. We inhabit every corner of the earth and have wrought just as much devastation on the seas–perhaps more. Technology has enabled us to dominate such a wide range of other species, and it has made human beings a uniquely devastating competitor.

Will we Destroy all Life on Earth?

Don’t give yourself airs.

Eradicate Gaia? Life is bigger and more robust than anything we are able to disrupt. No, the threat is not to Gaia but to ourselves. Life will eventually roar back, more diverse, more wondrously inventive than ever. But recovery from a mass extinction requires, typically, a few tens of millions of years. That’s nothing for Gaia, but for our grandchildren, 30 million years may try their patience.

There is life in boiling hot sulfur pits and life on the pitch black ocean floor, thriving under pressure that would crush a SCUBA tank, and life embedded in dry rock, equally deep under the land, living on who-knows-what. There are spores that were trapped in salt deposits 250 million years ago, recovered by scientists and brought back to life in the laboratory. To eliminate all life on earth is far beyond humanity’s destructive power for the foreseeable future.

But can we imperil the ecosystem that sustains human life? Quite possibly we can.

We may imagine the worst case scenario is that we destroy all of nature, lose all biodiversity and turn the earth into a vast farm to feed 20 or 30 billion humans. But it’s a good bet that this kind of world cannot be, and it is certain that we don’t know how to create it. Ecosystems are complicated and interdependent. From bees to bacteria, our farms and our pastures and livestock all sit atop ecosystems that we do not fully understand. Already, we are washing into the sea each decade topsoil that took 1,000 years to create . Farmers rent hives of pollinating bees, and the beekeepers are keeping them alive with increasing difficulty . For nitrogen-fixing bacteria, we have substituted saltpeter that we mine from the ground until there is no more of it left to mine.

Factory farming and antibiotics are two of mankind’s most successful and heavy-handed biological interventions. Each has worked spectacularly well for a few decades, and we have perhaps a few decades more before each will as spectacularly fail. We have that much time to create more sustainable replacements.

No, a world of monoculture to feed humans is not a viable world. We are animals. From an ecosystem we derived, and, for the foreseeable future, on a natural ecosystem we will continue to depend. We are not nearly smart enough to build an artificial ecosystem to support human monoculture. In all likelihood, the end of natural ecology would be the end of humanity.

Poets bemoan the loss of our spiritual connection to nature. Meanwhile, ecologists warn us that we are starving more than our spirits. We can’t engineer our way out of this. We don’t know how. We can’t understand or model ecosystems, so we have no idea how to move them in a given direction, even if humanity had the collective will to do so. If we destroy the ecosystem we have, we will have to wait for nature to take her course, and the wait is likely to be tens of millions of years.

Libertarian ethic

Many of my colleagues in the life extension community lean to libertarianism, and in some ways I am with them. I am frightened by our disappearing Bill of Rights, corporate takeover of the Free Press, exceptions to habeas corpus, wholesale domestic surveillance–and all this in service to perpetual war which most Americans want no part of.

But overpopulation and ecological collapse are problems that cannot be addressed individually. China realized decades ago that we cannot allow each family to decide how many children they wish to have. Still less can we condone men who impregnate women and walk away; and worst are the institutions that seek to preserve the morals of other people’s children by denying them knowledge of basic reproductive biology.

We will have to find ways to come together. The good news is that polls show consistently that people are aware of the threat and willing to put aside their own (short-term) economic interest to address it. (This despite concerted efforts to downplay the issue in the media.) The bad news is that present political structures will not address the problem. Our existing political order is, in fact, a big part of the problem. Politics is dominated by capitalist megacorporations that have their own agenda, and preserving the ecological foundation of human life is not part of it. Subversion of democracy by capitalism may have taken root in America and West Europe, but it is now a global blight.

We must work around government, the corporate media, the megacorporations and the whole capitalist economy. We must come together to consolidate and act on an existing consensus for

- A rapid transition to renewable energy

- Policies to encourage smaller families

- Limits to fishing, among other measures to protect the oceans

- Protections for natural habitats on land

I invite your thoughts and ideas about how to do this.

The more dramatic images in this column were taken from the book Overdevelopment, Overpopulation, Overshoot , published this year and available free online or for purchase in hard copy.

* Aging genes or the equivalent, combinations and epigenetic networks that work to ensure that our bodies weaken and ultimately self-destruct over time.

** Since they are hermaphrodites, each worm can breed without a partner, and so needs only 2 surviving offspring rather than 4 to double its population.